- Iterate

- Meet The Team

- As National Legalization Grows Likely, State-By-State Regulations are Still Squeezing Cannabis Entrepreneurs

As National Legalization Grows Likely, State-By-State Regulations are Still Squeezing Cannabis Entrepreneurs

So far, cannabis' return to the regulated market has been a bit of a cluster. A convoluted, complicated cluster. And while massive regulatory changes could be on the horizon, it’s one that has given the largest, first-to-market cannabis corporations a distinct advantage when it comes to expansion.

Thanks to a proliferation of partnership e-commerce tools, the formula for starting a successful consumer packaged goods (CPG) company in the U.S. isn’t all that complicated. For some products, all it takes to lay the groundwork is a high-engagement Instagram account.

But for entrepreneurs who want to break into a market estimated to top $24 billion in 2021 — legal cannabis — the startup process can be much more difficult. Instead of being able to test concepts and branding before launching, anyone working with cannabis has to first buy separate state licenses for cultivation, processing, and then distribution. All three can get extremely expensive, depending on the state. Only then can the work begin on creating a brand. It’s almost the exact opposite of how an entrepreneur would usually start a business.

And that’s only for companies who want to operate in one state. As soon as the time comes to expand into another market and become a multi-state operator (MSO), the licensing, real estate, and infrastructure process repeats itself. In essence, the system forces cannabis companies to start with a massive amount of initial capital and then expand with huge redundancies in the supply chain.

Marijuana became illegal in America in 1937 and was not made medically legal in any state until California became the first in 1996. So far, its return to the regulated market has been a bit of a cluster. A convoluted, complicated cluster. And while massive regulatory changes could be on the horizon — top Democrats in the Senate recently said they are putting together a plan for national reform this year — it’s one that has given the largest, first-to-market cannabis corporations a distinct advantage when it comes to expansion.

“This isn't necessarily a business where you can be a mom and pop shop and survive,” said Helene Servillon, a cannabis operator and investor who is the Founding Partner of Los Angeles-based VC firm JourneyOne Ventures. “That’s only going to be possible for a little bit because 80% of the national market, in my opinion, will eventually be run by huge multi-state operators.”

Plus, opportunities and resources vary widely by the state. Arizona, for example, legalized medical marijuana in 2012, does roughly $750M a year in medical sales, and nine MSOs command only roughly 30% of the state’s dispensaries. Voters agreed to open up the market to recreational sales in November 2020 and it became legal in January. There is money to be made on legal cannabis in Arizona.

Compare that to another state which recently voted for recreational legalization - New Jersey. The Garden State has had medical marijuana since 2012, but was incredibly restrictive for years and still only offers 12 vertical licenses (the ability for a company to own all aspects of its supply chain). As of January, New Jersey’s almost 9 million residents have access to just 13 total dispensaries.

How about California? The greenest state in the U.S. should have endless entrepreneurial opportunities, right? Yes and no. California has collected more than $1B in recreational cannabis tax revenue since 2016 and the top dispensaries in the state earn more than $20M a year. But the illicit market in California still outsells the legal one by close to $3B, in part due to a notoriously nightmarish licensing process that’s run by three separate regulatory bodies.

Three states, three remarkably different market needs.

Publicly-traded U.S. companies like Curaleaf ($13.5B market cap at time of publishing), Trulieve ($7.2B), and Green Thumb Industries ($6.9B) can live with these pricey expansion costs, but it’s become nearly impossible for a small-time player to create a multi-state cannabis business selling THC products.

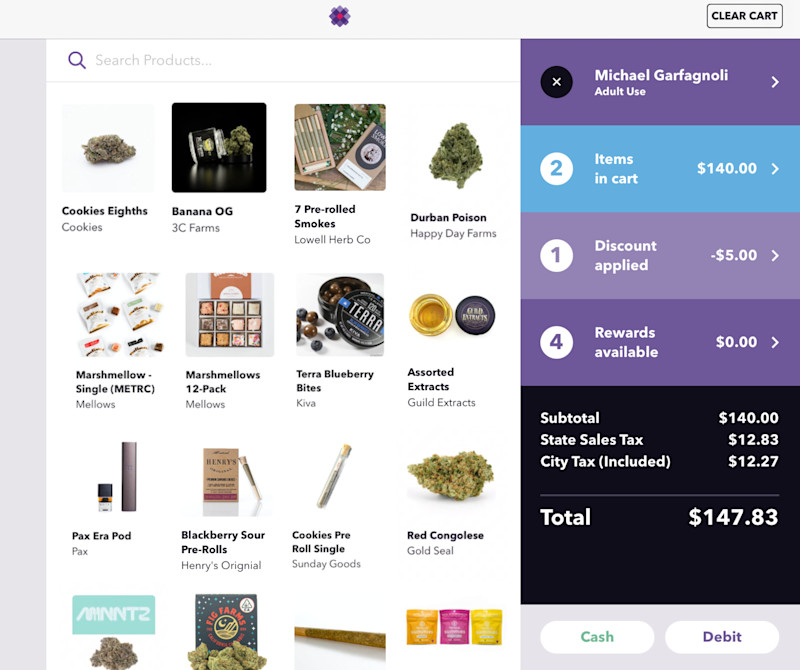

This dynamic has forced many in the space to create businesses that don’t directly grow or cultivate cannabis. Even then, some of those companies, like San Francisco-based Meadow, have found it more effective to stick to one state. Started in 2014 by David Hua and three other technical co-founders, Meadow became the first cannabis company to be accepted into startup accelerator Y Combinator in 2015. The next year, the startup launched an SaaS platform for retail and delivery, and today, is an all-in-one POS system for dispensaries. Meadow has technology that can handle California’s complicated tax and compliance systems and says it has doubled its annual GMV the last several years. Its goal is to own 20% market share in CA in 2021.

The 13-person company is succeeding in California, but even that has had to be a choice.

“We have great interest in going to other markets, other states, but even California still hasn't nailed regulations. They're still changing them,” said Max Esdale, Meadow’s Head of Compliance & Community. “The level of changes we've seen here, we expect it to also happen in other states, and if we go rushing into another area, we leave our flank exposed.

“By focusing on California and developing a product that meets the needs of the operators and businesses here, we've managed to switch over a large number of our current partners from competitors who got caught up with expanding into other states. There's how much you can grab, sure, but at this point it’s more about how much you can keep.”

Servillon, the investor and operator who also leads supply chain and brand licensing for strategy firm Greater Holdings and has helped cannabis companies expand into new markets like Nevada, Michigan, and Massachusetts, finds that building the right team in cannabis requires leadership with both experience in the field and a true speciality. A founder with a deep regulatory and compliance background, for example, or a technical team who can run a point of sale system strong enough to withstand intense regulatory requirements (cannabis is regulated as a pharmaceutical) while building seamless API integrations.

“The market dynamics are really tricky because a good decision today might only be a good decision for the next five years,” Servillon said. “Five years from today, the cannabis industry will look very different.”

With all that being said, the rigidity of these regulations also isn’t necessarily helping the MSOs either. These companies have a lot of money but are also being forced to spend it on extremely expensive bets in new markets. Curaleaf, for example, is the largest cannabis company in the U.S. for a reason — it has operations in 23 states, harvests from more than 20 cultivation sites, and owns another 30 processing sites. Forget the costly licensing fees. Even just the physical real estate and infrastructure of those 50+ cultivating and processing plants costs tens of millions of dollars.

If you could ship cannabis across state lines like other products, there’d be no reason to build an indoor grow facility in a climate like Illinois. Or individual distribution centers. Or redundancies in the supply chain.

So if and when the U.S. government ends the country’s 80+ year old national cannabis ban, the growth dynamics in the industry could completely flip. Large companies could be stuck offloading redundancies while smaller players will be able to try quick replications of traditional CPG growth models. Suddenly, CMOs and brand strategists and cross-state logistics experts would become among the most valuable employees of a cannabis startup. Theoretically, a more inclusive second Green Rush would emerge.

--

The Org is a professional community where transparent companies can show off their team to the world. Join your company here to add yourself to the org chart!

In this article

The ORG helps

you hire great

candidates

Free to use – try today