- Iterate

- Meet The Team

- ‘Captive Audience’ Meetings are in the NLRB’s Crosshairs. Here’s How a Ban on the Popular Management Tactic Could Impact Union Campaigns.

‘Captive Audience’ Meetings are in the NLRB’s Crosshairs. Here’s How a Ban on the Popular Management Tactic Could Impact Union Campaigns.

Table of contents

We spoke with Cornell University union expert Kate Bronfenbrenner about the NLRB’s latest push to end a common union-busting tactic, and how it could impact how union campaigns are run.

What do captive audience meetings look like?

Captive audience meetings vary by workplace, but they often share a similar tone. The meetings are typically run by a company’s CEO or another top executive who will present “all the negative things that are going to happen if a union comes in,” Bronfenbrenner said in an interview with The Org. “It's where all the propaganda against unions happens, and the big threats about closing.”

The gatherings are required, occur on company time and can persist throughout a union campaign in the lead-up to an official union vote—even weekly, Bronfenbrenner explained. Her 2009 study found that, on average, employers held nearly 11 captive audience meetings per year in organizing workplaces.

In captive audience meetings, leaders “tend to isolate and humiliate those who support the union. And if workers try to ask questions, they either refuse to allow them to speak, or they very often will intimidate them, or threaten them, and make fun of them,” Bronfenbrenner added. “These are very intimidating settings…and they will often make the union supporters stand up, and they'll divide them for their support in the union.”

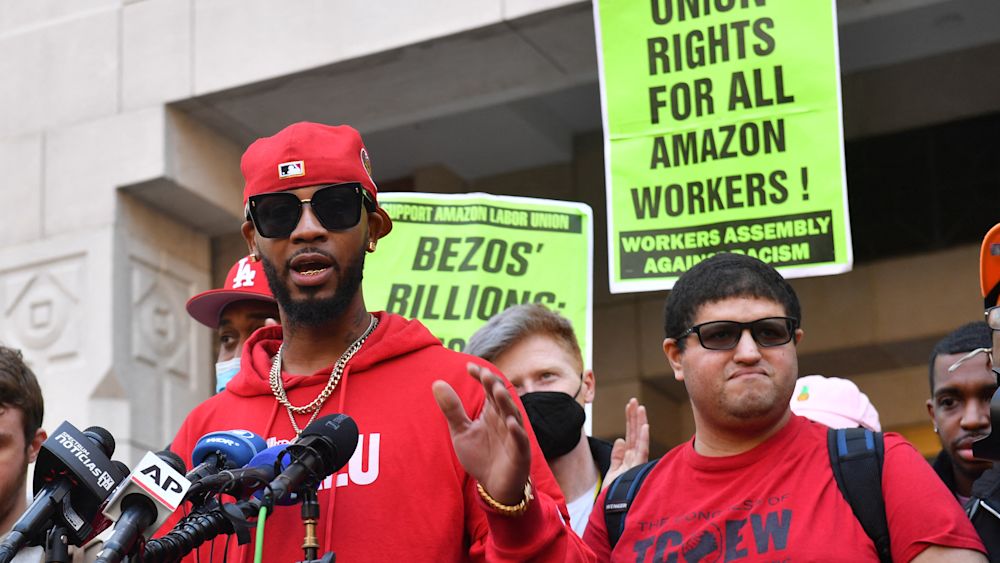

Amazon management has reportedly relied on these types of meetings over the past year. The Seattle-based e-commerce giant has labeled mandatory anti-union sessions as “training” or “small group meetings” at warehouses with organizing efforts in Bessemer, Alabama and Staten Island, New York, according to The New York Times. The Staten Island cohort won its vote last week—forming the first ever official Amazon union—as the Alabama warehouse awaits the results of its second union vote.

During the pandemic, many of these meetings have occurred over Zoom or other video conferencing software. But Bronfenbrenner says the virtual replacements are less effective in scaring workers away from organizing.

Will the ban happen?

It’s too early to say. Abruzzo, a Biden appointee who began her four-year term in July, said she is preparing a formal brief to submit for NLRB members’ consideration. As concerns about regulating corporate speech mount, Abruzzo’s push could face “monumental opposition from the business lobby and right-to-work groups,” Politico asserted. Bronfenbrenner points out that the conservative-leaning Supreme Court could strike down a change in labor policy.

It’s also worth noting that, in some states, the fate of these meetings have precedent in the public sector. In Ohio, for example, these mandatory meetings have been illegal since the 1980s in local and state government offices, per a decision by the state’s employment relations board. In 2010, Oregon became the first and only state to prohibit all employers from requiring workers to attend meetings with a religious or political agenda (including anti-union meetings), and the legislation survived several legal challenges, including one launched in 2020 by the Trump administration’s NLRB. Connecticut’s state legislature is currently debating a similar bill that could outlaw such meetings.

How might employers respond to a ban?

Employers would have to rethink how they clamp down on organizing efforts. Without the “captive audience” meeting at their disposal, Bronfenbrenner thinks that company leaders will rely more heavily on one-on-one meetings between managers and employees–where the “most intense intimidation happens,” she said. (Importantly, she noted: “intimidating and threatening workers is illegal”—per the 1935 National Labor Relations Act.)

In using this tactic, employers will instruct supervisors to discourage organizing, some going so far as to evaluate a supervisor's performance based on how many of their direct reports vote against the union.

“Supervisors know that they're going to lose their job unless they make sure they have all ‘no votes’ in their department,” she explained. “They talk to workers, if not every day, at least twice a week, and they ask the workers, ‘which way are you going to vote? Which way is everybody else gonna vote?’ And they threaten the workers if they aren't gonna vote.”

Sign up now: Stay up to date, level up and hire better with our behind the scenes newsletters at the world’s top startups.

The ORG helps

you hire great

candidates

Free to use – try today